The 2016 9-string Fanned Fret Harp Guitar Project

Construction Details:

Site Map

A modern update of two old ideas:

The Nine-String Fanned Fret Harp Guitar is a modern update of two very old ideas which date to the late 16th century, the use of fanned frets and the addition of extra strings to the "norm" of a six-course instrument. The tuning is as follows:F#1 B1 [ E2 A2 D3 G3 B3 E4 ] A4. Note that the tuning of the six strings of the conventional six-string guitar is retained, so that legacy repertory is playable, but that they are sandwiched by one additional treble string and two additional bass strings.

Although a six-course instrument such as the six-string guitar or the six-course lute actually does represent a logical limit for instrument design because of the physical properties of thickness, thinness, tension and breaking points of the strings, nevertheless lute and guitar players have been adding extra strings to their instruments anyway since the 16th century, in order to expand their available tonal resources, and many such designs have been created and played over the last five centuries. The availability of custom length and diameter strings is a limiting factor of course, but nowadays a wide selection of long lute strings in every diameter are available from both the La Bella and D'Addario string manufacturers.

Extra strings (beyond the usual number of four to six) always must break the above-mentioned logical limit in some way, and for that reason a number of different strategies have been used, of which the most common is to make the additional strings longer and unfretted, so that they only produce a single pitch. Of this type were all versions of the Baroque lute, and similarly, the modern "Harp Guitar" has only six fretted strings, with any number of added mono-pitched bass strings. While many players find these instruments satisfactory for their musical purposes, they also have specific musical deficiencies: chiefly that a complete chromatic range of bass notes is missing, and secondly that the design is inefficient in only getting one note out of each bass string, while the much more useful and efficient fretted strings each offer a complete chromatic range of an octave and a half.

However, if a conventional straight-fret design is used, at a length which is convenient for achieving whatever the highest treble string might be, then if low bass strings are included on the fingerboard with the other fretted strings, they will be far too short to be truly functional. They must be extremely thick, and they do not play in tune when fretted. The common ten-string classical guitar design with straight frets suffers from this defect: although the low basses are fretted, the length is not optimal for the pitches to which they are usually tuned, and they function best only as open strings.

All of these instruments with added, unfretted bass strings are actually hybrids, part guitar and part bass harp, with two distinctly different technical processes going on: (1) fretted strings, and (2) unfretted strings. It is worth considering this question: how would you optimize the tuning of a bass harp for complete harmonic availability of all chromatic notes? And note that while traditional harps ("celtic" harps, etc.) are strictly diatonic, with seven pitches to the octave, the concert harp used in orchestras actually has seven foot pedals each of which globally changes the inflection of all the strings of a particular pitch class. Some smaller harps have hand levers on each string, which accomplish the same thing in a more limited way. These pedals and levers do the same job as frets. The principle is the same, in fact, as with the fretted clavichord. The modern concert harp has 47 strings, most of which do have variable inflection, and this large number of strings is possible because (1) the strings are of widely differing lengths and (2) they are tuned diatonically rather than in fourths or fifths as is common for instruments of the guitar-lute-viol class.

The point of this is to say that even harp players have found it necessary to develop technical means of changing the pitches of the strings, and are not content with strings that play only one pitch (it is splitting hairs to mention that on some concert harps, there are a very few extreme bass and treble notes which cannot be inflected). So the true emulation of a bass harp in the lower register of a hybrid harp-guitar, then, would require some additional mechanical means of changing the pitch of each string, except in the cases of those musicians who are perfectly happy playing vanilla diatonicisms. Such mechanisms have been tried on extended range guitars. The disadvantage is that they are typically inconvenient to change on the fly.

Fanned Frets:

The fanned fret design was invented in the late 16th century in the form of a lute-like instrument called the Orpharion. The fanned fret design permits the treble strings to be as short as necessary, and the low bass strings to be as long as necessary, while the intermediate strings lie along a continuum between the extremes, so that each string may have the optimum length for its particular pitch. The Orpharion was not a lasting success and the fanned fret concept lay abandoned until the late 20th century, when electric guitar builder Ralph Novak patented his own fanned fret design. Although Novak has been rightly criticized for patenting an idea which clearly was not his original invention, he had the passion and vision to promote his design and it became widely known. When his patent expired, the field exploded with fresh activity and creativity, mostly among builders and players of electric guitars. Classical players, led by Paul Galbraith, have adopted a more conservative design with a modest fan and eight strings, known as the "Brahms Guitar". The Brahms Guitar has a typical difference between longest and shortest strings of about 1-3/8" (3.5 centimeters).On discovering that many electric guitar players are playing on fanned fret designs which at their most extreme may have up to six inches (15 centimeters) of difference between the longest and shortest strings, Jack observed that it should be possible to add a ninth string to the "Brahms Guitar" design, by extending the width of the fan. However, even a casual look at either Jack's 2013 9-string Prototype, or at the more successful 2016 9-string Fanned Fret Harp Guitar, shows that there are many, many possible variables for such a design. Optimally a planned series of prototypes would have answered many questions, but that would have been a prohibitively expensive proposition. Hence the 2013 prototype was designed to answer as many questions as possible, which made it improbable that it would be a total success in itself. It did, however, answer many questions and pointed the way to the later design which turned out to be very practical and playable.

(To this rosy assessment of the new instrument I must add, later, the caveat that I had pain in shoulders, elbows and wrists for about two years while I was adjusting to playing it. There may have been other good reasons for that which can't be blamed on the guitar, because I am no spring chicken, but it cannot go without mention.)

Our Luthier:

Salvador Castillo has built over 500 guitars to date, sold them all over the world, and we have observed them to get better and better. We have been visiting his shop since 2006. Not only have we (Jack and Frances) owned six of Salvador's instruments ourselves, we know several other musicians who play his guitars.Castillo is a native of Paracho, Michoacan (the great musical-instrument manufacturing center of Mexico since the 16th century), and the son of a luthier, Ramiro Castillo, who continues to make guitars himself in another shop across the street.

The most profound innovation Castillo has made, since the construction of our seven-strings in 2012, has been to adopt the use of "lattice bracing" instead of the Torres-style fan bracing which was the standard for 150 years. Lattice bracing was invented by the Australian luthier Greg Smallman some forty years ago, and since then many variations have been invented by other luthiers.

The following table shows a comparison of the specifications of the 2013 Prototype and those of the 2016 Nine-String Fanned Fret Harp Guitar:

| 2013 Nine String Prototype Details | 2016 Nine String Fanned Fret Harp Guitar |

|---|---|

| Top wood: Engelmann Spruce (Picea Engelmanii), with conventional fan bracing. Engelmann is a little less expensive than European. |

Top wood: European Spruce (probably "Carpathian") (Picea Abies) with lattice bracing. |

| Back and Sides: Palo Escrito (Dalbergia Paloescrito)

Palo Escrito is the least expensive rosewood variety, but a very beautiful wood all the same. |

Back and Sides: Cocobolo (Dalbergia Retusa) Possibly the best rosewood variety still commonly available, Cocobolo is very dense and gives very solid basses, a good choice for a guitar with an F#1 string. (Note that the recent CITES treaty has made international travel with rosewood instruments complicated.) |

| Fingerboard: Granadillo (Platymiscium Yucatanum)

Our two seven-string guitars of 2012 (Frances still plays hers, but I sold mine to pay for the nine-string) had ebony fingerboards which checked at the sound-hole end - an easy repair by filling with black epoxy, but the movement also caused minor cracks in the tops next to the uppermost part of the fingerboard. Granadillo, according to several luthiers we spoke to, is more stable than the ebony now available. I asked for some minimal fingerboard markers as an afterthought. However, the map of the extended range fingerboard was difficult to learn and I wished I had put more fret markers. |

Fingerboard: Granadillo (Platymiscium Yucatanum) A nicely figured piece left a natural red, unstained. The fingerboard inlays, in conch shell and abalone, give fret markers for the entire fingerboard, a great help to learning the new patterns. (On the other hand, the fret marker layout on the 2016 build was more ornamental than practical, and I had to learn IT as well as the fingerboard, and I would probably go for a more conventional pattern of fret markers next time, or at least a pattern designed more to identify the positions more clearly. I would NOT try to play an extended-range fingerboard with no fret markers, it would be very difficult to orient oneself and to learn the harmonic grammar of the additional strings, which is hard enough as it is.) |

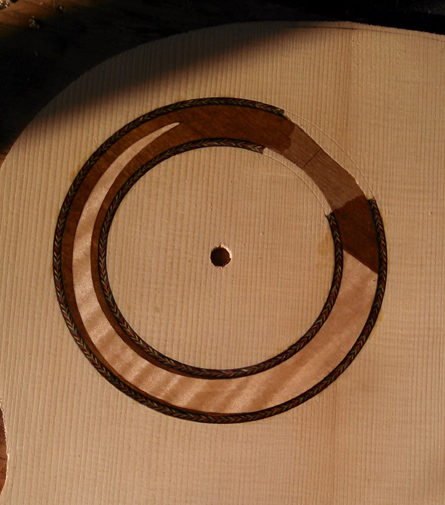

| Rosette: Stock | Rosette: Jack's own drawing realized by Castillo in figured woods. |

| Soundhole location: centered conventionally. The problem that emerged was that the point of the angled bridge, where the A4 string is anchored, was so close to the transverse bar which marks the end of the fan brace system (just below the sound hole) that the A4 string did not make the top vibrate enough. |

Soundhole location: moved into the upper bout. This innovation allowed the transverse bar to be placed farther away from the end of the bridge, and, combined with the lattice bracing and other modifications, allowed the entire top to vibrate more freely, as the bridge is in the center of the vibrating field. However, although this, in combination with other details, resulted in a guitar with a beautiful sound and a better response from the high A string, it does have a weakness. The top is quite thin and the lattice bracing quite delicate. When I was experimenting with string tension, the bridge went up and down with different tensions of strings, making it very difficult to get the string tension, the variable setbacks and setforths at nut and saddle, and the action all optimized, because each variable affected the others. Now that I have that all set (not that a little more work couldn't be done on the intonation) it is not a problem, but it was a problem in various stages of solution for the first two years. |

| Tuners: Pegheds brand planetary pegs,

look like Flamenco or violin pegs, but have gears inside.

Although these tuners have worked very well on other guitars of ours, and look very elegant, it turned out that they did not work well for the low basses, which require a finer tuning ratio. Pegheds does manufacture a bass tuner as well, but they are much larger, and it didn't seem like a good detail to put both sizes on one instrument. |

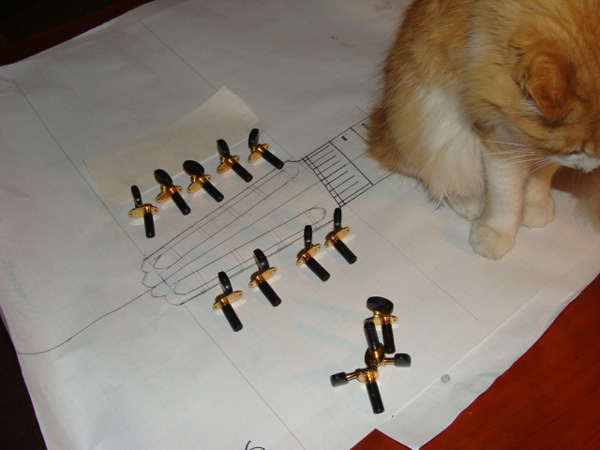

Tuners:

Schertler

These Schertler's are the only single-unit classical guitar tuners on the market besides the Pegheds: all others come with three tuners locked together on a single plate. The 3-on-a-plate design is specifically for six-string guitars, and they must be cut and spliced for 7, 8, 9, or 10-string guitars. Although it was necessary to buy 12 units (i.e., two sets) of the Schertlers to obtain the necessary nine, they are very nice tuners with a 20:1 gear ratio which is much more satisfactory for the low basses than were the Pegheds. |

| No pickup was installed in the Prototype. | Although I had a four piezo discs installed under the top of the the new nine-string, with a jack and wiring harness, I had some problem with an unidentifiable vibration noise, and I removed the whole pickup assembly. Now I am using an external piezo pickup with an external signal processor, and I don't think that I will ever install an internal pickup in any of my guitars again. |

| Fingerboard Width at nut: 69mm (2-5/8"+) This was a mistaken attempt to learn whether the guitar would in fact be playable with a narrow string spacing (7.5mm). It was not, which was a major problem. It would have been far better to build the fingerboard as wide as might have been possibly useful, because it would always be possible to reduce the spacing of the strings and leave some of the fingerboard unused by constructing a new nut and a notched saddle, but it is not possible (duh) to increase the spacing on a narrower fingerboard, except by removing a string, which is eventually what I did. A further comment on left-hand string spacing: the classical guitar standard spacing is minimum 8mm between strings, center to center, and 9mm is more common; 8.5 mm may also be found. However, on steel string and electric guitars, 7.5mm and even less, down to less than 7 mm may be found. It seems that a player who has become used to one particular spacing is usually uncomfortable with any other. Electric guitar players complain about the wide necks of classical guitars; classical players complain that they cannot play cleanly on narrow spacings. Advice: if you are having an extended range guitar built, go with the spacing you are already comfortable with, or verify that you will be happy with a different spacing by getting hold of a six-string guitar with that spacing and practicing on it for a time. Fear of a very wide neck leads to the logical idea of trying a narrower string spacing, but it's a dubious move. |

Fingerboard Width at nut: 80mm (3-1/8"+) This width allows 9mm between strings and a generous 4mm at the sides, far more satisfactory. Naturally it is more difficult to stretch all the way across than any narrower fingerboard, but that's the price of having nine strings. Yes, there are some hypothetical chord positions that cannot be reached on this account, but they can't be played on any other guitar either. A lesson learned from the prototype is that the bass strings F#1 and B1 are significantly thicker that the E2 string, and they need a little more room between them. A graduated string spacing might be a possibility. Look how wide the string spacing is on electric basses. |

| Length of A4 string (shortest): 56 centimeters (22-1/16th"). I thought that this short length might allow the use of a thicker string for a more robust sound. (Requintos are often even shorter, as short as 52 c.) However, the simultaneously-resulting short lengths of the E4 and B3 strings gave somewhat poor intonation in the upper registers. This could be fixed with proper saddle compensation, but the saddle is too narrow to permit this, and my temporary-fix conversion to an eight-string does not permit it either. I don't know that the string length of 56c is unworkable because of the tuning issues; because of various obstacles and the fact that it will require some serious work on the bridge which I am hesitant to do myself, I never got around to adjusting the intonation of the Prototype, and it plays quite out of tune above about the 8th fret. I have a future plan to make it permanently into an eight-string with wider string spacing. My present eight-string conversion is a cludge, because there are still nine string holes in the bridge. Making a new nut was easy, but I had to make a notched saddle in order to make eight strings line up, and saddle compensation is impossible until I replace the entire bridge and saddle assembly with a new one with 8 string holes and a wider saddle to permit compensation. In contemplating this project, I have been developing a possible idea for an entirely different bridge and saddle design, each string having an individual saddle adjustable for string length in order to fine-tune the intonation at the 12th fret, but I have not yet figured out how such a design could also include the desirable element of adjustable action height for each string without a metal screw being part of it, which seems rather inelegant for a classical guitar. |

Length of A4 string: 60 centimeters (23-5/8"). The standard length of the A4 of the Brahms Guitar is 61.5 centimeters, and some A4s have been as long as 63 centimeters. However, these are very thin and fragile strings. 60 may be the best compromise; at any rate it works very well on this particular guitar. On the new 9-string I was able to do both nut and saddle compensation, and the intonation is far better, although chords above the 12th fret are a little weird. |

| Length of F#1 string (lowest): 68 centimeters (26-3/4").

This was calculated to be the same as the second fret of a short scale (30" or 76c) electric bass. It is the same length chosen for the low E1 on a 10 string fanned fret classical-type guitar built a few years ago for a guy named Fred Fernseher, who designed it and had it built by a luthier who was not identified. That was the only other classical guitar of this extreme fanned-fret type ever built (probably). From the perspective of the usual classical guitar with a length of 65c, 68c is very long indeed, and since that length had been used by Fernseher for a string pitched a whole step lower yet, it was a reasonable assumption that it should work. This assessment was backed up by the opinions of some of the players on the sevenstring.org forum, who, however, are mostly electric players who have little experience with nylon strings, and may be forgiven on that account. The fact is, it was not long enough after all, and I had to conclude that this was just a mistake that nobody had yet tested in practice in a real-world gig situation. The string was so thick that it clicked on the frets and did not play in good tune. It sounded great played open, and it sounded acceptable when playing a single note on any one fret, but attempting to play any two fretted notes in rapid succession made an unacceptable clicking noise. |

Length of F#1 string (lowest): 72 centimeters (28-5/16"+).

This length performs much better. I am using an .075" diameter string. I am now sure that a 70c length would have been a mistake (too short), and although the 72c length does indeed work very well, there is also a great possibility that 75c would work better on a hypothetical future build in terms of sound alone, although there is an equally great question about whether it would be playable, just as there was for this guitar until was built. A future build with a fan 60c to 75c would be about equal to the maximum fan anyone has attempted on electric guitars. But, considering the physical difficulty I had getting comfortable with playing this instrument, it is unlikely that I will ever have a guitar built with the longer string length. A distinct bonus of the 72c F# is that the resulting longer proportionate lengths of the B1 (70.5c) and E2 (69c) give a very fine sound to these bass strings also. The length of the median string, D3, is 66c, and the length of the G string is 64.5c, the B is 63c, and the E is 61.5c, and so the treble section actually feels like a short-scale. It is emphatically NOT like playing a guitar with a 72c scale, but actually feels quite normal under the fingers, surprisingly so, considering the contrary case of the 2013 Prototype, where the higher "right angle fret" makes the fingerboard somewhat less comfortable. |

| String Spacing at Bridge: 10.5mm. This was another mistaken experiment. I was worried that the span of nine strings would be also too wide for the right hand. In fact, the narrower spacing was very difficult to play. When I modified the guitar to an eight-string, I built a notched saddle with a wider string spacing. |

String Spacing at Bridge: 11.5mm. This is both conventional and correct. |

| Location of "right angle fret": #5 On Fred Fernseher's fanned fret 10 string, the "right angle fret" is number 12, that is, exactly at the half-way point of the string, and dividing the fan equally between the bridge and the nut. (See pic.) This makes for an extreme and uncomfortable angle at first position; the angles of bridge and nut are the same. When the nut is angled so extremely, the left elbow must be brought closer to the body in such a way that it does not support the connection between the left wrist and the left shoulder. With the usual "Brahms Guitar" design, the "right angle fret" is number 8. With the less extreme fan design of the Brahms guitar, first position ought to be quite comfortable, although I have never played one. However, first position on the 2013 Nine String Prototype was uncomfortable enough to prompt a decision to move the "right angle fret" toward the nut on the 2016 build. |

Location of "right angle fret": #3 This allows first position to be quite comfortable. Although the upper frets run out into extreme angles and require a slightly different playing technique, the angled frets are actually ergonomically better in the upper positions than they are slanted the other way in the lower positions. The fanned frets have no effect on technique up to about the 10th fret. |

2016: Cocobolo back with pickup temporarily in place to show location of exit jack. I later removed this internal pickup system entirely.

2016: Schertler

Tuners: (There are three extras looking for a home, for another ERG.)

2016: Schertler

Tuners: (There are three extras looking for a home, for another ERG.)

9-string Project Home

9-string Project History Page

Site Map